Study Guide: Lighting

Lightning

Lightning is an electrical discharge caused by imbalances within clouds, or between storm clouds and the ground.

It is not only spectacular, it’s dangerous. Over 2,000 people are killed worldwide by lightning each year. Hundreds more survive strikes but suffer lasting symptoms, including memory loss, dizziness, weakness, numbness, and other life-altering ailments. Strikes can cause cardiac arrest and severe burns, but nine of every ten people who are struck survive.

How does lightning form?

During a storm, colliding particles of rain, ice, or snow inside storm clouds increase the electrostatic imbalance between the clouds and the ground. Scientists don’t know why this happens, but one theory is that during storms the heavier negatively charged particles can collect near the lower edges of clouds, while lighter positively charged particles collect near the top.

At the same time, tall, electrically conductive objects on the ground, such as buildings, trees, and tall teachers can become positively charged, creating an electrical imbalance with the clouds. This can trigger an electric current between the two oppositely charged objects.

How hot is lightning?

Technically, lightning is simply the movement of electrical charges and does not have a temperature.

However, just as an electric heater uses electrical resistance to convert electric energy into heat energy, the atmosphere’s resistance to the movement of the electricity in lighting causes the air—and anything else lightning passes through—to heat up.

A good conductor of electricity has a low resistance, and won’t heat up as much as a poor conductor. Air happens to be a terrible conductor of electricity. That’s usually a good thing for us, but air gets extremely hot when lightning passes through it. In fact, lightning can heat the air it passes through to $50,000°F$. That’s 5 times hotter than the surface of the Sun!

When lightning strikes a tree, the heat instantly vaporizes any water in its path causing trees to explode.

Now you can starting winning bets. Ask someone which they think is hottest, the surface of the Sun or some of the air right here on Earth during big storms.

How does lighting cause thunder?

As the air the lighting passes through resists the electric current, the surrounding air rapidly expands and vibrates. This in turn creates the thunder we hear.

Most materials expand as they heat up, and the faster they heat up, the faster they expand. Near-instant heating results in near-instant expansion, and near-instant expansion makes one helluva lot of noise!

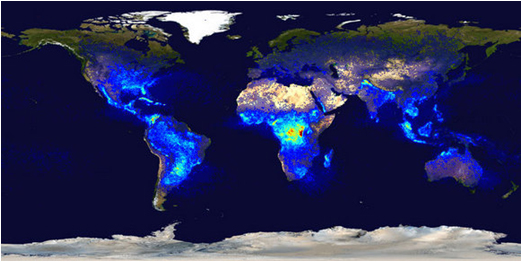

Where does lighting strike?

Globally, most lighting strikes occur in the tropical regions of Africa, South America and Asia. In North America, most lighting strikes occur in Florida. This is because hot moist weather conditions are an ideal environment for forming huge amounts of atmospheric static electricity.

Source: Florida Disaster

How likely are we to get struck by lightening?

Lightning strikes kill more people each year in North American than either tornadoes or hurricanes. Contrary to common belief, lightning can and often does strike the same place twice. The average person in North American has about a $ 1 : 5,000 $ chance of being struck by lightning during their lifetime. These are far better odds than the odds of winning the lottery.

How Far Away is the lightning?

We can use an estimate of the speed of sound to tell how far away lightning is. Sound travels about one mile in five seconds. Therefore, count the seconds between the lightning flash and the thunder. For every five seconds you count, lightning is about one more mile away.

How do we protect ourselves from lightening?

A good safety rule is to remember that if you can hear the thunder, you are close enough to be struck by lightning. Even if it is not raining where you are, lightning can still reach you.

Lightning can travel as far as 10 miles from the storm, and has been observed up to 25 miles away. Don’t forget that lighting is traveling at the speed of light, which is several million miles per hour faster than you can blink.

- Whenever you see lightning, seek shelter as soon as possible.

- Get away from water. Contrary to popular belief, water itself does not conduct electricity, but the minerals and impurities in water do. If you are swimming in a mountain lake, a lighting strike anywhere on that lake can shock you.

- Get away from tall objects, such as isolated trees, tall metal structures, or any other object that may attract lighting.

- Get inside a building. All well-constructed buildings are grounded by metal rods that conduct a lightning bolt’s electricity into the ground. Homes may also be grounded by plumbing, gutters, or other materials. Note that even inside a building, you should not touch running water or use a landline phone during a storm.

- Get inside a car. Cars are havens from lightning—but not for the reason that most believe. Tires conduct electricity, as does the vehicle’s metal frame. The good news is that these components safely transfer the electrical charge into the ground and away from the occupants.

Types of Lightning

Most lightning never leaves the clouds. It travels between differently charged areas of a cloud, or from one cloud to another.

Cloud-to-ground lightning is also common. About 100 strike the Earth’s surface every second. Each lightning bolt can contain one billion volts of electricity.

A typical cloud-to-ground lightning bolt begins when a step-like series of negative charges, called a stepped leader, races downward from the bottom of a storm cloud toward the Earth along a channel at about 200,000 mph (300,000 kph). Each of these segments is about 150 feet (46 meters) long.

When the lowermost step comes within about 150 feet (46 meters) of a positively charged object, it is met by a climbing surge of positive electricity, called a streamer, which can rise up through a building, tree, or person.

When the two connect, an electrical current flows at near the speed of light into the Earth, and a visible flash streaks upward at about 200,000,000 mph (300,000,000 kph).

Other rare forms can be sparked by extreme forest fires, volcanic eruptions, and snowstorms.

The cause of ball lightning, a small, charged sphere that floats, glows, and bounces along oblivious to the laws of gravity or physics, is still a scientific mystery.

Some cloud-to-ground lightning bolts are called “positive lightning,” a type that forms in the positively charged upper surfaces of clouds. These strikes reverse the charge flow. They are far stronger and destructive. Positive lightning can stretch far across the sky and strike “out of the blue” more than 10 miles from where it formed.